What medieval attitudes tell us about our evolving views of sex

[ad_1]

In the illuminating and entertaining blog Going Medieval, Eleanor Janega, a medievalist at the London School of Economics, upends prevalent misconceptions about medieval Europe. These misunderstandings include that people didn’t bathe (they did) and that these were the Dark Ages*. Her new book, The Once and Future Sex, is subtitled “Going Medieval on Women’s Roles in Society,” and that’s exactly what she does—if by “going medieval” you intend the pop culture meaning of “dismembering in a barbaric manner” which, despite her protestations, you probably do.

Her main thrust, in the blog and in the book, is that it’s easy and convenient for us to envision medieval times as being backward in every way because that makes modern times seem all that much more spectacular. But not only is this wrong, it’s dangerous. Just because life is definitely better for women now than it was then, that doesn’t mean our current place in society is optimal or somehow destined. It’s not.

Progress did not proceed in a straight arrow from bad times then to good times now. Maintaining that things were horrible then deludes us into thinking that they must be at their pinnacle now. Janega lays out this argument in the introduction and then spends the bulk of the text citing evidence to bolster it.

Blame the Greeks

The first chapter describes how medieval Europeans got their ideas about women, sex, beauty, and… well, generally everything from the Greeks. Greeks viewed men as the default humans; women were viewed spiritually as fallen men (Plato) and physically as inside-out men (Galen). Then Christianity and its doctrine of Original Sin came along, which did not exactly induce men to see women in a more favorable light.

“Augustine’s message was that even when a man disobeyed God, it was probably because a woman had convinced him to do so,” she notes. Men wrote down these ideas about women and then spent centuries teaching them to other men in universities and monasteries, where there were definitively No Girls Allowed.

(Nuns were permitted to read, study, and think, and the surviving records of women who did so, like Hildegard of Bingen [1098–1179] and Christine de Pizan [1364–c.1430], suggest that they did not view their own natures quite like men did. But educated women were rare, and surviving writings by or about them are rarer still.)

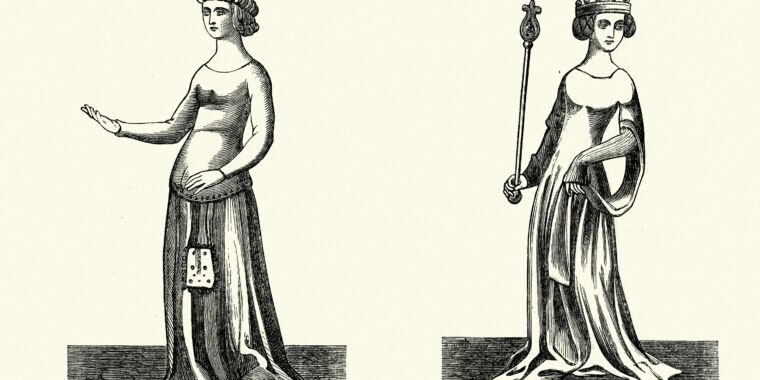

Then there’s a chapter on beauty standards for women, which mandated golden tresses, milky-white skin, and rosy cheeks. The adjectives were lifted directly from Dares Phrygius, a contemporary of Homer’s who purportedly witnessed the Trojan War, and they’ve remained unchanged until… basically now. Then, as now, women were supposed to naturally have this appearance; God forbid they put any time, money, or effort into it. (Quite literally—using make-up was considered among the gravest of sins).

Medieval men did like a potbelly on their women, though. This is the opposite of today’s preference for chiseled abs, but both features denote the same trait: wealth. Medieval women sporting potbellies clearly had enough to eat, and today’s flat-bellied women clearly have enough leisure time to work out.

[ad_2]

Source link