Collector discovered Isaac Newton’s lost personal copy of Opticks

[ad_1]

Peter Harrington Rare Books

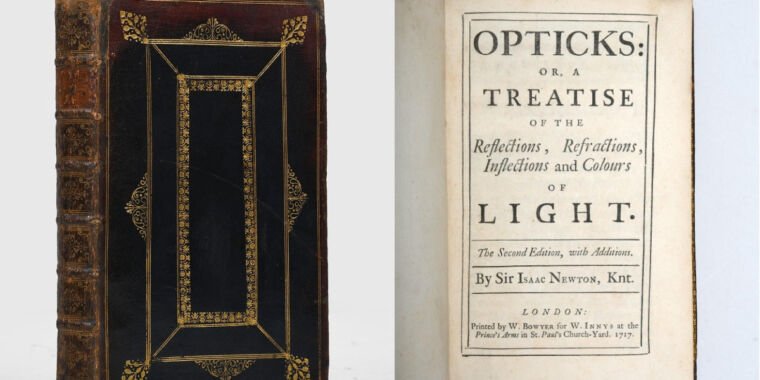

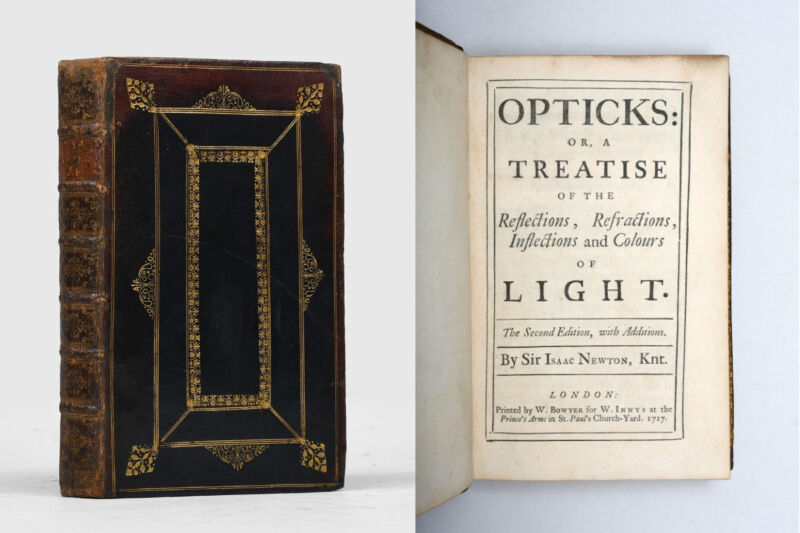

David DiLaura, an emeritus professor at the University of Colorado, was working on his comprehensive bibliography listing every significant scientific volume on optics when he made an unexpected discovery. The copy of Isaac Newton‘s seminal treatise Opticks that he had purchased some 20 years before turned out to be from Newton’s own personal library, believed lost for many decades. The book will go up for sale at the Rare Books San Francisco Fair, February 3–5, 2023, with a price of $375,000.

“It’s becoming increasingly rare for an author’s own copy of a book of this magnitude to fly under the radar for so many years,” said Pom Harrington, owner of Peter Harrington Rare Books, which is handling the sale. “When DiLaura bought this copy more than 20 years ago from an English rare book dealer in West Sussex, neither buyer nor seller had any idea of its history. DiLaura has described his discovery as ‘a once-in-a-collector’s-lifetime event,’ and it really is. Collectors and rare book dealers love a good tale of rediscovery, especially one which came to light—quite literally in this case—in the way this one did.”

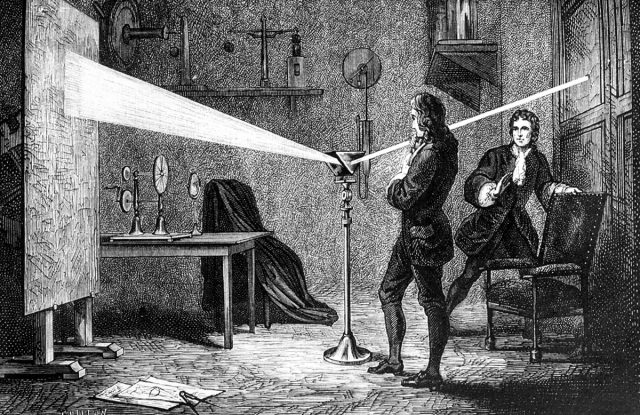

Newton is justly most famous for his Principia and the co-invention of calculus, but he also had a longstanding interest in optics. For instance, he once stuck a long sewing needle (bodkin) into his eye socket between the eye and bone and recorded the colored circles and other visual effects he saw. And as a young scientist at the University of Cambridge, he conducted what is known as his experimentum crucis, darkening his room one sunny day and making a hole in the window shutter to let a narrow beam of sunlight into the room. Then he placed a glass prism in the sunbeam and observed the rainbow bands of light in the color spectrum.

When he placed a second prism upside-down in front of the first, the band of colors recombined into white sunlight, thereby proving his hypothesis that white light is made up of all the colors of the spectrum combined. Based on his theory of color, Newton concluded that refracting telescope lenses would be plagued by chromatic aberrations (the dispersion of light into colors) and built the first practical reflecting telescope, using reflective mirrors rather than lenses as the objective to solve that problem. He gave a demonstration of his telescope to the Royal Society in 1671.

Newton was also at the center of a heated debate regarding whether light was a particle or a wave—a debate that had raged for millennia. Pythagoras, for example, was staunchly “pro-particle,” while contemporaries ridiculed Aristotle for daring to suggest that light travels as a wave. Empirical observations of the behavior of light contradicted each other. On the one hand, light traveled in a straight line and would bounce off a reflective surface. That’s how particles behave. But it also could diffuse outward, and different beams of light could cross paths and mix. That’s wave-like behavior.

By the 17th century, many scientists had generally accepted the wave nature of light, but there were still holdouts in the research community—among them Newton, who argued vehemently that light consisted of streams of particles that he dubbed “corpuscles.” In 1672, colleagues persuaded Newton to publish his conclusions about the corpuscular nature of light in the Royal Society’s Philosophical Transactions. He seemed to assume that his ideas would be greeted with unanimous cheers and was offended when Robert Hooke and the Dutch physicist Christiaan Huygens criticized his conclusions.

All of these insights and more eventually formed the basis of Newton’s final treatise, Opticks, first published in 1704. At the time, the English astronomer John Flamsteed declared that it “makes no noise in town,” unlike when Principia was published. But it still represented a major contribution to optical science, ranking alongside Johannes Kepler’s Astronomiae Pars Optica and Huygens’ Traité de la Lumière. Also unlike Principia, Opticks was written in English instead of Latin, making it far more readable.

[ad_2]

Source link